Abstract

The record of past climate highlights recurrent and intense millennial anomalies, characterised by a distinct pattern of inter-polar temperature change, termed the ‘thermal bipolar seesaw’, which is widely believed to arise from rapid changes in the Atlantic overturning circulation. By forcing a suppression of North Atlantic convection, models have been able to reproduce many of the general features of the thermal bipolar seesaw; however, they typically fail to capture the full magnitude of temperature change reconstructed using polar ice cores from both hemispheres. Here we use deep-water temperature reconstructions, combined with parallel oxygenation and radiocarbon ventilation records, to demonstrate the occurrence of enhanced deep convection in the Southern Ocean across the particularly intense millennial climate anomaly, Heinrich Stadial 4. Our results underline the important role of Southern Ocean convection as a potential amplifier of Antarctic warming, and atmospheric CO2 rise, that is responsive to triggers originating in the North Atlantic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over at least the last 800,000 years, millennial climate variability has been characterised by a distinct pattern of inter-hemispheric temperature change, accompanied by changes in the cryosphere and the global biogeochemical and hydrological cycles. This dominant mode of ‘rapid’ climate variability has been described conceptually in terms of a ‘thermal bipolar seesaw’1,2, whereby gradually rising temperatures over Antarctica represent a ‘convolution’ of their more abrupt Northern Hemisphere counterparts. Antarctic temperatures thus appear to vary as the inverse of Greenland temperatures, albeit with a slight lag (~200 years)3 and with a ~1000 year time-constant. Note that the thermal bipolar seesaw is defined here as a pattern of inter-hemispheric temperature change, rather than a hypothetical mechanism. According to this conceptual model, Antarctica takes a few centuries to respond to the initiation of a seesaw event, upon which it gradually catches up with the inverse of Greenland temperature change (though it is notable that Greenland and Antarctic temperature proxies appear to follow similar cooling trends later in interstadials4). The canonical explanation for these ‘seesaw’ events is that they reflect the impacts of abrupt changes in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), causing a reduction in the northward meridional heat transport in the Atlantic, and a consequent (gradual) increase in heat transported to Antarctica across the putative ‘thermal/dynamical barrier’ provided by the Southern Ocean and Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) e.g.2,5,6,7. Despite the elegance of this simple explanation, it has proven difficult to reconcile with a detailed account of the underlying physical processes, particularly those responsible for controlling northward and southward oceanic and atmospheric meridional heat transport, and influencing the exchange of heat between the ocean and atmosphere8. Indeed, not all numerical model simulations involving a suppressed AMOC exhibit a thermal bipolar seesaw response9, and when they do, these typically achieve only ~50% of the observed temperature change e.g.8,9,10,11. Based on idealised numerical model experiments, it has been suggested that by enhancing heat loss from the ocean to the atmosphere, Southern Ocean convection may have been crucial for achieving a higher amplitude Antarctic warming, while also contributing to the associated rise in atmospheric CO2 (ref. 12). Here, we provide direct observational support for this proposal using combined proxy reconstructions of deep-ocean temperature and ‘ventilation’ (oxygenation and radiocarbon ages) spanning Heinrich Stadial 4 (HS4) in the deep sub-Antarctic Atlantic (see Fig. 1), an event that was accompanied by particularly intense ice-rafted debris deposition in the North Atlantic13, and evidence for AMOC collapse14. Our results reveal the ‘fingerprint’ of enhanced heat- and gas exchange in the deep Southern Ocean, in parallel with rising Antarctic temperature and atmospheric CO2, as observed in numerical model simulations where enhanced Southern Ocean convection actively contributes to an increase in both Antarctic temperature and atmospheric CO2 concentration.

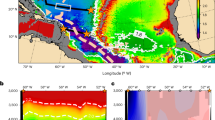

Location of core MD07-3076Q (red star) is shown with the modern ocean temperature (shading)49, and dissolved O2 concentration (contours)50; a shown as deep-water temperature Tdw (at greatest depth) in a stereographic projection of the Southern Ocean, and b in a meridional transect of the South Atlantic along 14° W.

Results

Despite the existence of core-top Mg/Ca-temperature calibrations for a variety of benthic foraminifer species, the reconstruction of relatively subtle deep-water temperature variability in the past remains a significant challenge. Only a handful of records that capture centennial-millennial-scale deep-water temperature changes associated with e.g. Dansgaard–Oeschger (D–O) climate variability currently exist, e.g.15,16,17,18,19, and it remains to be shown that such signals can be reproduced by parallel measurements in multiple (co-existing) benthic foraminifer species. Our down-core benthic Mg/Ca measurements reveal a consistent pattern of variability in both Uvigerina sp. and Globobulimina affinis, that indicates a cooling across HS4 (Fig. 2). Observed Mg/Ca-temperature sensitivities in these species would imply that the observed cooling is of order ~1 °C. Obtaining absolute temperature values requires extrapolating from existing calibrations, slightly beyond the range of available calibration points at the low temperature end (i.e., <0.9 °C; see supplementary Fig. S1). Nevertheless, using existing calibrations for G. affinis20 and Uvigerina sp.21, consistent absolute temperatures can be obtained for both species when Uvigerina sp. Mg/Ca is corrected by −0.137 mmol/mol. This correction (equivalent to 1.5 °C) does not depend significantly on the choice of temperature calibration for Uvigerina sp., e.g.22,23, though we adopt the calibration of ref. 21 as this is the most consistent with new core-top measurements that we have obtained in parallel with our down-core measurements (see Supplementary material). The consistency we observe between the two benthic foraminifer Mg/Ca records, despite the different temperature sensitivities of these species, strongly supports the robustness of the temperature signals they reveal, though here we place greater emphasis on their trends and range of variability than on the absolute values that are obtained. Below we discuss the associations and implications of the deep Southern Ocean cooling that we observe across HS4, with a particular emphasis on ocean-atmosphere heat- and carbon exchange.

a Polar planktonic foraminifer, N. pachyderma (left coiling) abundance (black solid line and open circles, Nps %), compared with the EDML Antarctic ice-core temperature proxy, δ18Oice (blue line)4, and with deep-water temperature variability estimated from combined Mg/Ca measurements from two benthic foraminifer species (open red circles, with cubic spline and 95% confidence intervals, based on 0.6 °C 1 sigma uncertainty, are indicated by the solid and dashed red lines respectively; note inverted y axis). b benthic Mg/Ca measurements (G. affinis, solid black circles and spline; Uvigerina sp., crossed red circles and spline; error bars represent 2% analytical reproducibility), compared with the Greenland ice-core temperature proxy δ18Oice (light blue line, with dark blue running mean)51. Vertical shaded bar indicates the approximate timing of Heinrich Stadial 4 (HS4).

Discussion

When our deep-water temperature record is compared with parallel reconstructions of deep-water oxygenation and radiocarbon ventilation (obtained from the same sediment sequence), a clear pattern of cooling combined with enhanced air–sea gas equilibration in local deep water is observed (Fig. 3). These trends directly parallel the rise in Antarctic air temperature and atmospheric CO2 across HS4 (Fig. 3), and reflect the ‘fingerprint’ of enhanced Southern Ocean deep convection, permitting the exchange of heat and gas (including CO2) between the atmosphere and a large volume of southern-sourced deep water24. While a local cooling might also be expected due to a simple reduction in the local representation of relatively warm northern-sourced deep-water (as has been inferred at this site previously25), a parallel increase in ventilation would not. The co-occurrence of cooling and improved ventilation therefore suggests a change in the ventilation rate of southern-sourced deep water, rather than a simple removal of northern influence. We suggest that this interpretation accounts for the lack of a strong rebound in deep-water temperature at the end of HS4, despite a rapid change in northern-sourced deep-water delivery to the Southern Ocean at this time25. Indeed, it can be seen in Fig. 3 that deep-water temperature, oxygen, and radiocarbon ventilation all show a ‘tailing off’ after HS4, rather than an abrupt shift, consistent with a predominantly southern hemisphere association.

Data from MD07-3076Q are compared with composites of simulations performed with the UVic and LOVECLIM Earth system models (experiments U-TrS and L-TrS from ref. 12), and atmospheric CO2 change. a Atmospheric CO2 (light blue filled circles and dashed line, and solid red line showing 3-point smoothing), compared with deep-water radiocarbon ventilation inferred from B-P radiocarbon age offsets37. b Reconstructed oxygenation based on authigenic U/Mn ratios of foraminiferal coatings37 (solid blue circles and line), compared with simulated Southern Ocean deep-water oxygenation (solid orange line), based on a composite of outputs over 55–10° W, 50–75° S and 3300–4000 m. c Reconstructed deep-water temperature based on benthic Mg/Ca (filled black circles, and b-spline solid line), compared with simulated Southern Ocean deep-water temperature (solid orange line). d Greenland δ18Oice event stratigraphy compared with simulated maximum Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) stream-function (solid black line).

A similar ‘fingerprint’ is also apparent in idealised numerical model experiments where enhanced Southern Ocean convection is encouraged by reducing the buoyancy of Southern Ocean surface waters12. In these model simulations, a much stronger Antarctic temperature and atmospheric CO2 rise is achieved with enhanced Southern Ocean convection than without (Fig. 3). The additional warming is associated with enhanced ocean-to-atmosphere heat fluxes, which are correlated with increased mixed layer depths around the Southern Ocean (Fig. 4), and cannot be accounted for by an enhanced eddy-driven ‘bolus heat flux’ in the model’s surface ocean layer for example26. Similar changes in mixed layer depth, corresponding with a diagnostic combination of increased oxygenation and cooling in the deep ocean, are also observed in other idealised model simulations that reproduce large-amplitude millennial-scale Antarctic temperature and CO2 anomalies27,28. The observed association of Antarctic warming, with lower temperature, higher oxygen, and lower radiocarbon ages in the deep sub-Antarctic Atlantic, is therefore consistent with enhanced deep-ocean convection that released heat from the ocean interior to the atmosphere, and contributed to Antarctic warming. However, the processes leading to enhanced deep-ocean convection in the Southern Ocean during Heinrich Stadials remain poorly constrained, and could include changes in surface buoyancy (as employed in our model scenarios12), or alternatively the strengthening or poleward shift of the Southern Hemisphere westerlies29,30,31.

a Impact of enhanced convection on deep-water oxygenation (3300–4000 m depth), based on the difference between composites of UVic and LOVECLIM simulations of HS4 with- (Tr–S) and without (Tr) enhanced Southern Ocean convection; b as for (a) but for deep-water temperature; c atmosphere to ocean heat flux (shading; negative values indicate increased heat flux out of the ocean), and mixed layer depth (MLD, contours) for composite of UVic and LOVECLIM simulations of HS4, without enhanced Southern Ocean convection; d as for (c), but for simulations with enhanced Southern Ocean convection.

Classically, millennial-scale climate anomalies associated with the ‘thermal bipolar seesaw’ have been conceptualised in terms of lateral heat transport, associated with meridional mass movement in the Atlantic Ocean7, and a presumed slow ‘pseudo-diffusive’ heat transfer across the Southern Ocean and ACC2. However, our findings resonate with a recent analysis8 that emphasised the important role played by ocean interior heat storage, as modulated by continual heat uptake at low latitudes32 and its subsequent release, e.g., through deep convection, at high latitudes24. Thus, thermal bipolar seesaw events might be conceived of as representing the effects of alternating heat loss from the ocean interior to the atmosphere, either via the North Atlantic (during ‘Greenland interstadials’) or the Southern Ocean (during ‘Greenland stadials’), in order to balance continuous heat uptake at low latitudes. The resulting dynamic, of alternating deep convection anomalies in the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean (i.e., a ‘ventilation seesaw’, as posited for millennial events during the last deglaciation33,34), would augment the previously identified role of ocean interior heat accumulation during periods of reduced AMOC32, which eventually ‘leaks’ out into the Southern Ocean surface via the sub-tropical thermocline. Heat transport from the sub-tropical thermocline to the Southern Ocean surface and atmosphere would be achieved by eddy transport, abetted by amplifying sea ice albedo feedbacks8. We therefore propose that AMOC slow-down/collapse increased the magnitude of the ocean interior heat pool available for warming the Southern Ocean (mainly just below the thermocline), and that deep convection increased its rate of delivery to the southern polar region by enhancing the rate of heat loss from both the intermediate and deep ocean. A schematic for the envisaged ‘seesaw’ is presented in Fig. 5.

An alternating dominance of buoyancy (and heat) loss from the North Atlantic (right) and Southern Ocean (left), balances buoyancy and heat input at low latitudes, for a Greenland-interstadial, and b Greenland-stadial conditions. Enhanced air–sea exchange associated with water-mass conversion in the Southern Ocean enhances heat- and carbon loss from the southern abyssal cell, and increases its oxygen and radiocarbon content (note that the northern cell will typically remain warmer and better ventilated than the abyssal southern cell). Red arrows at the ocean surface indicate buoyancy fluxes of different approximate magnitudes. Weakened overturning cells are indicated by dashed continuous arrows; strengthened cells by heavy solid continuous arrows.

The additional contribution from deep convection may be difficult to identify consistently in numerical model experiments because convection in the Southern Ocean does not always occur spontaneously in idealised freshwater ‘hosing’ experiments employed to derive hypothetical ‘stadial’ analogues. This in turn may reflect an absence of appropriate atmospheric teleconnections or sub-grid scale processes in the models, or it could reflect unexpected far field impacts of ‘hosing’ (freshwater addition to the surface ocean), e.g., helping to stratify the Southern Ocean and impede deep convection there35. Taken together with the fact that ‘hosing’ experiments intending to mimic thermal bipolar seesaw behaviour typically fail to obtain sufficiently large temperature anomalies over Antarctica, e.g.8,9,10,11, except when enhanced Southern Ocean convection is encouraged12, this could imply that AMOC perturbations associated with bipolar seesaw events may not have been forced by massive freshwater forcing. This contention might be supported by the observation that cold (stadial) conditions in the North Atlantic consistently precede the ice-rafting pulses that are typically interpreted to indicate periods of anomalous freshwater delivery to the North Atlantic36. It might be further supported if other means of modulating the strength of the AMOC (e.g., via sea ice, ice-sheet height and/or wind influences) do not tend to impede Southern Ocean convection. Regardless of the presumed causes of AMOC variability, our observations demonstrating the occurrence of deep convection in the Southern Ocean during HS4 (as already proposed for millennial events during the last deglaciation34, and as surmised for millennial variability throughout Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 337,38), suggest that a more detailed study of the mechanisms responsible for spontaneous deep convection in the Southern Ocean during periods of AMOC collapse is needed. In this respect, a possible steer comes from recent work using a conceptual model to investigate the closure of the global overturning circulation39,40, which suggested that a north–south ‘thermal bipolar seesaw’ might be seen as a by-product of a north–south ‘ventilation seesaw’, which in turn would arise out of a requirement to close the ocean’s buoyancy budget, subject to density anomalies in one hemisphere relative to the other. Accordingly, northern and southern convection might be seen as alternating ‘buoyancy release valves’ for the global ocean. In this conceptual framework, changes in the formation rate (mass flux) of Antarctic Bottom Water might not be a key element of the proposed north-south ventilation seesaw; of greater importance would be the changing proportion of upwelling Circumpolar Deep Water that loses buoyancy and returns to the abyssal ocean near Antarctica, versus the proportion that gains buoyancy and flows northward, ultimately to resupply the formation of NADW through buoyancy loss in the North Atlantic instead.

The occurrence of deep convection (and/or enhanced air-sea exchange) in the Southern Ocean during North Atlantic stadials (i.e. periods of reduced AMOC14) has further implications for atmospheric CO2, as well as global energy balance on millennial time scales. Our findings support the proposal that deep convection in the Southern Ocean helped to amplify atmospheric CO2 change during North Atlantic stadials12, and that a loss of respired and/or ‘disequilibrium’ carbon from the deep Southern Ocean during North Atlantic stadials37 was driven at least in part by changes in air–sea gas exchange (as distinct from changes in vertical mass overturning rates or the export of biologically fixed carbon for example)41. Finally, it has not escaped our attention that the occurrence of enhanced Southern Ocean convection during periods of reduced AMOC is also likely to bear on the evolution of global ocean heat content across thermal bipolar seesaw events, with further implications for global average surface air temperatures and ‘climate sensitivity’ on millennial time scales. Accordingly, if global energy balance can be pushed out of equilibrium on millennial time scales due to ocean circulation/convection changes that result in a redistribution of heat between the ocean and the atmosphere42, then the sense and magnitude of global surface air temperature change during AMOC perturbations will depend at least in part on the Southern Ocean’s capacity to release heat from the ocean interior, when heat loss from the North Atlantic (and the AMOC) is suppressed32.

Detailed observations of mean ocean temperature change across D–O and Heinrich stadials are needed to confirm the net effect on global energy balance due to ocean convection changes; however, existing data from the last 39 kyr42 already suggest that the global ocean heat content tends to increase during stadials, consistent with many numerical model simulations8,32. Based on our conclusion that deep Southern Ocean convection (and heat release to the atmosphere) increased during HS4, this would suggest that the global ocean heat content has been overwhelmingly influenced by ocean heat accumulation in intermediate-depth waters, which indeed appear to have warmed during stadials17,19, rather than heat loss through deep convection. In conjunction with emerging estimates of mean ocean temperature42,43, reconstructions of the evolving ‘thermal fingerprint’ of the ocean interior will be invaluable for developing an understanding of how shifting ocean convection patterns can influence global energy balance, and thus modulate global climate change on centennial to millennial timescales.

In summary, multi-species benthic foraminifer Mg/Ca reconstructions, combined with radiocarbon and oxygenation data, reveal the ‘fingerprint’ of deep-ocean convection in the South Atlantic across HS4, confirming a role for Southern Ocean convection in Antarctic warming, and atmospheric CO2 rise, associated with the thermal bipolar seesaw. The inability of many numerical ‘hosing’ experiments to reproduce the observed amplitude of Antarctic temperature and CO2 change across Heinrich stadials could be due to a lack of deep convection in the Southern Ocean in these models, perhaps due to missing sub-grid scale processes, misrepresented atmospheric teleconnections, or possibly due to excess buoyancy being supplied via the North Atlantic through ‘freshwater hosing’ (contra the freshwater forcing paradigm)35. These results bear directly on the proposed sensitivity of modern global energy balance and carbon cycling to changes in Southern Ocean convection24, and suggest that accurate projections of future climate-carbon cycle feedbacks are likely to rely on an improved representation of the complex interplay between evolving winds, buoyancy, and mass transport, in the Southern Ocean.

Methods

Foraminifer-based proxy reconstructions

Combined proxy reconstructions of deep-water temperature and ‘ventilation’ (oxygenation and radiocarbon age) have been generated in sediment core MD07-3076CQ (3777 m; 44.1° S, 14.2° W; see Fig. 1), for which an age-model is derived from a stratigraphic alignment of warming phases recorded in sea surface temperature proxies and Antarctic ice cores placed on the AICC2012 age scale25. Radiocarbon ventilation reconstructions are based on benthic versus planktonic foraminifer radiocarbon age offsets37. This metric avoids uncertainties regarding atmospheric 14C ages during HS437, and provides an estimate of the mean time-scale for CO2 exchange between the deep ocean and the atmosphere, as compared with that for the local surface ocean. Oxygenation reconstructions are based on foraminiferal U/Mn ratios37, which are interpreted to reflect the increased deposition of authigenic Uranium under more oxygen depleted conditions37,44,45,46. We combine these proxies for ocean-atmosphere gas exchange with additional reconstructions of ocean-atmosphere heat exchange, based on deep-water temperature estimates derived from benthic foraminiferal Mg/Ca ratios. In order to assess the reproducibility of our reconstructed deep-water temperature signal we make use of parallel measurements in two infaunal benthic foraminifer species, Uvigerina sp. and G. affinis. We make use of infaunal species in order to minimise possible contributions to Mg/Ca variability from deep-water carbonate ion saturation changes15,16,23. Samples of 4–10 individual foraminifera were oxidatively cleaned according to the protocol of ref. 47, prior to dissolution and analysis by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry according to the protocol described in ref. 48. The analytical internal reproducibility is better than 2%. The efficiency of cleaning to remove external contaminant phases was screened on the basis of Fe/Ca ratios, which here remain below 0.05 mmol/mol.

Core-top calibration measurements

Several new core-top measurements have been performed using unstained (i.e., not necessarily living) specimens of Uvigerina sp. picked from latest Holocene material in order to assess our ability to reproduce existing calibration trends. Although none of the core-top samples were radiocarbon dated, studies on nearby sediment cores indicate that sedimentation rates >5 cm/kyr are expected at all locations, yielding probable ages for the samples of a few centuries at most. Temperatures for calibration were drawn from in situ water column measurements performed at the time of sample recovery. The locations and results are summarised in the accompanying Supplementary information.

Numerical model simulations

The records generated from MD07-3076CQ are compared with freshwater hosing experiments performed with the Earth System models of intermediate complexity LOVECLIM (L-) and UVic (U-) under MIS 3 boundary conditions12. In four experiments, transient changes in freshwater supply are applied to the North Atlantic (varying between 0.1 and 0.15 Sv) to simulate North Atlantic stadials (-Tr), and in two of these experiments a negative freshwater flux (−0.1 to −0.2 Sv) is also added into the Southern Ocean to trigger deep-ocean convection (-TrS). Composites of the experiments with (L-TrS and U-TrS) and without (L-Tr and U-Tr) Southern Ocean salt flux are shown for the time period encompassing HS4.

Data availability

New data presented in this study are available in Supplementary information, and from the PANGAEA database at: https://www.pangaea.de. Numerical model outputs are published at Research Data Australia at: https://doi.org/10.26190/5efe7c8c75bd5.

References

Barker, S. et al. 800,000 years of abrupt climate variability. Science 334, 347–351 (2011).

Stocker, T. F. & Johnsen, S. J. A minimum thermodynamic model for the bipolar seesaw. Paleoceanography 18, PA1087 (2003).

Wais Divide Project Members et al. Precise interpolar phasing of abrupt climate change during the last ice age. Nature 520, 661, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14401 (2015).

EPICA community members. One-to-one coupling of glacial variability in Greenland and Antarctica. Nature 444, 195–198 (2006).

Barker, S. et al. Interhemispheric Atlantic seesaw response during the last deglaciation. Nature 457, 1097–1102 (2009).

Schmittner, A., Saenko, O. A. & Weaver, A. J. Coupling of the hemispheres in observations and simulations of glacial climate change. Quat. Sci. Rev. 22, 659–671 (2003).

Seidov, D. & Maslin, M. Atlantic Ocean heat piracy and the bipolar climate see-saw during Heinrich and Dansgaard-Oeschger events. J Quat. Sci. 16, 321–328 (2001).

Pedro, J. B. et al. Beyond the bipolar seesaw: toward a process understanding of interhemispheric coupling. Quat. Sci. Rev. 192, 27–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2018.05.005 (2018).

Kageyama, M. et al. Climatic impacts of fresh water hosing under Last Glacial Maximum conditions: a multi-model study. Clim. Past 9, 935–953 (2013).

Stouffer, R. et al. Investigating the causes of the response of the thermohaline circulation to past and future climate changes. J. Clim. 19, 1365–1387 (2006).

Ganopolski, A. & Rahmstorf, S. Rapid changes of glacial climate simulated in a coupled climate model. Nature 409, 153–158 (2001).

Menviel, L., Spence, P. & England, M. H. Contribution of enhanced Antarctic Bottom Water formation to Antarctic warm events and millennial-scale atmospheric CO2 increase. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 413, 37–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2014.12.050 (2015).

Hemming, S. R. Heinrich events: massive late pleistocene detritus layers of the North Atlantic and their global climate imprint. Rev. Geophys. 42, 1–43 (2004).

Henry, L. G. et al. North Atlantic ocean circulation and abrupt climate change during the last glaciation. Science 353, 470–474, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf5529 (2016).

Skinner, L. C. & Elderfield, H. Rapid fluctuations in the deep North Atlantic heat budget during the last glaciation. Paleoceanography 22, PA1205 (2007).

Skinner, L. C., Shackleton, N. J. & Elderfield, H. Millennial-scale variability of deep-water temperature and d18Odw indicating deep-water source variations in the Northeast Atlantic, 0–34 cal. ka BP. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 4, 1–17 (2003).

Weldeab, S., Friedrich, T., Timmermann, A. & Schneider, R. R. Strong middepth warming and weak radiocarbon imprints in the equatorial Atlantic during Heinrich 1 and Younger Dryas. Paleoceanography 31, 1070–1082, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016pa002957 (2016).

Repschläger, J., Weinelt, M., Andersen, N., Garbe-Schönberg, D. & Schneider, R. Northern source for Deglacial and Holocene deepwater composition changes in the Eastern North Atlantic Basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 425, 256–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.05.009 (2015).

Marcott, S. A. et al. Ice-shelf collapse from subsurface warming as a trigger for Heinrich events. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13415–13419, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1104772108 (2011).

Weldeab, S., Arce, A. & Kasten, S. Mg/Ca- CO2−-temperature calibration for Globobulimina spp.: a sensitive paleothermometer for deep-sea temperature reconstruction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 438, 95–102 (2016).

Roberts, J. et al. Evolution of South Atlantic density and chemical stratification across the last deglaciation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 1–6, http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1511252113 (2016).

Bryan, S. & Marchitto, T. Mg/Ca-temperature proxy in benthic foraminifera: new calibrations from the Florida Straits and a hypothesis regarding Mg/Li. Paleoceanography 23 (2008).

Elderfield, H., Yu, J., Anand, P., Keifer, T. & Nyland, B. Calibrations for benthic foraminiferal Mg/Ca palaeothermometry and the carbonate ion hypothesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 250, 633–649 (2006).

de Lavergne, C., Palter, J. B., Galbraith, E. D., Bernardello, R. & Marinov, I. Cessation of deep convection in the open Southern Ocean under anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 278–282, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2132 (2014).

Gottschalk, J. et al. Abrupt changes in the southern extent of North Atlantic Deep Water during Dansgaard-Oeschger events. Nat. Geosci. 8, 950–954, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2558 (2015).

Stocker, T. F., Timmermann, A., Renold, M. & Timm, O. Effects of salt compensation on the climate model response in simulations of large changes of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. J. Clim. 20, 5912–5928 (2007).

Schmittner, A., Brook, E. J. & Ahn, J. In Ocean circulation: mechanisms and impacts (eds A. Schmittner A. et al.) 315–334 (AGU Monograph, 2007).

Schmittner, A. & Galbraith, E. Glacial greenhouse-gas fluctuations controlled by ocean circulation changes. Nature 456, 373–376 (2008).

Buizert, C. et al. Abrupt ice-age shifts in southern westerly winds and Antarctic climate forced from the north. Nature 563, 681–685, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0727-5 (2018).

Menviel, L. et al. Southern Hemisphere westerlies as a driver of the early deglacial atmospheric CO2 rise. Nature Communications 9, 2503, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04876-4 (2018).

Gottschalk, J. et al. Mechanisms of millennial-scale atmospheric CO2 change in numerical model simulations. Quat. Sci. Rev. 220, 30–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.05.013 (2019).

Galbraith, E. D., Merlis, T. M. & Palter, J. B. Destabilization of glacial climate by the radiative impact of Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation disruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 8214–8221, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069846 (2016).

Broecker, W. S. Palaeocean circulation during the last deglaciation: a bipolar seesaw? Paleoceanography 13, 119–121 (1998).

Skinner, L. C., Waelbroeck, C., Scrivner, A. & Fallon, S. Radiocarbon evidence for alternating northern and southern sources of ventilation of the deep Atlantic carbon pool during the last deglaciation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5480–5484, http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1400668111 (2014).

Brown, N. & Galbraith, E. D. Hosed vs. unhosed: interruptions of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation in a global coupled model, with and without freshwater forcing. Clim. Past 12, 1663–1679, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-12-1663-2016 (2016).

Barker, S. et al. Icebergs not the trigger for North Atlantic cold events. Nature 520, 333–338 (2015).

Gottschalk, J. et al. Biological and physical controls in the Southern Ocean on past millennial-scale atmospheric CO2 changes. Nat. Commun. 7, 11539, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11539 (2016).

Jaccard, S. L., Galbraith, E. D., Martínez-García, A. & Anderson, R. F. Covariation of deep Southern Ocean oxygenation and atmospheric CO2 through the last ice age. Nature 530, 207–210, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16514 (2016).

Thompson, A. F., Hines, S. K. V. & Adkins, J. F. A Southern Ocean mechanism for the interhemispheric coupling and phasing of the bipolar seesaw. J Clim. 32, 4347–4365 (2019).

Hines, S. K. V., Thompson, A. F. & Adkins, J. F. The role of the Southern Ocean in abrupt transitions and hysteresis in glacial ocean circulation. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 490–510, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018pa003415 (2019).

Skinner, L. C., Muschitiello, F. & Scrivner, A. E. Marine reservoir age variability over the last deglaciation: implications for marine carboncycling and prospects for regional radiocarbon calibrations. Paleoceanogr. Paleoclimatol. 34, 1807–1815, https://doi.org/10.1029/2019pa003667 (2019).

Baggenstos, D. et al. Earth’s radiative imbalance from the Last Glacial Maximum to the present. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 14881–14886, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1905447116 (2019).

Bereiter, B., Shackleton, S., Baggenstos, D., Kawamura, K. & Severinghaus, J. Mean global ocean temperatures during the last glacial transition. Nature 553, 39–44 (2018).

Boiteau, R., Greaves, M. & Elderfield, H. Authigenic uranium in foraminiferal coatings: a proxy for ocean redox chemistry. Paleoceanography 27, https://doi.org/10.1029/2012pa002335 (2012).

Klinkhammer, G. & Palmer, M. R. Uranium in the oceans: where it goes and why. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 55, 1799–1806 (1991).

Skinner, L. et al. Rare earth elements in the service of palaeoceanography: a novel microanalysis approach. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 245, 118–132 (2019).

Barker, S., Greaves, M. & Elderfield, H. A study of cleaning procedures used for foraminiferal Mg/Ca paleothermometry. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 4, 84078 (2003).

Yu, J., Day, J. A., Greaves, M. J. & Elderfield, H. Determination of multiple element/calcium ratios in foraminiferal calcite by quadrupole ICP-MS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosys. 6, Q08P01 (2005).

Locarnini, R. A. et al. NOAA Atlas NESDIS Vol. 73 (eds Levitus S. & Mishonov, A. V.) (Maryland Ocean Climate Laboratory, 2013).

Garcia, H. E. et al. In NOAA Atlas NESDIS Vol. 75 (eds Levitus S. & Mishonov A. V.) 27 (U.S Government Printing Office, 2004).

Svensson, A. et al. A 60,000 year Greenland stratigraphic ice core chronology. Clim. Past 4, 47–57 (2008).

Acknowledgements

L.S. acknowledges funding from NERC grant NE/J010545/1. L.M. acknowledges funding from the Australian Research Council grant FT180100606. J.G. acknowledges support from the German Research Foundation (grant GO 2294/2-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. designed the study. L.B. and M.G. collected the benthic foraminifer Mg/Ca data. L.M. performed the numerical model simulation, and L.S. and L.M. analysed the model outputs. L.S. wrote the manuscript with input from L.M., J.G., and M.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Peer review information Primary handling editor: Joe Aslin Deep Southern Convection in HS4 12 August 2020

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Skinner, L., Menviel, L., Broadfield, L. et al. Southern Ocean convection amplified past Antarctic warming and atmospheric CO2 rise during Heinrich Stadial 4. Commun Earth Environ 1, 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00024-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00024-3

This article is cited by

-

Plate tectonics controls ocean oxygen levels

Nature (2022)

-

Onset and termination of Heinrich Stadial 4 and the underlying climate dynamics

Communications Earth & Environment (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.